Patrick Phillips recently wrote a well-researched non-fiction book called Blood at the Root. His book is hard to read because it is historical in nature, and it describes a time of racism and injustice that is impossible to fathom in our modern world. The subject is difficult to write about, whether in a book or in an article because sometimes the present is scared of and desperately wants to forget about a dark past. This is not Sugar Hill’s legacy, but it literally happened across the Chattahoochee River in Forsyth County. It can be said, however, that a little bit of this awful history passed through Sugar Hill on its way to Cumming.

Sugar Hill has served as a crossroads since it began as Orrsville, a mercantile and ferry crossing community, in the 1830s. Native Americans crossed through our community, as well as European settlers working their way westward. Even in the early 1900s, the Sugar Hill community served as a crossroads between the railroad town of Buford and Cumming – the latter longing for the railroad and the benefits of passengers and cargo passing through their rural community. It was a long journey by wagon, even for hauling bags of sugar, from Buford to Cumming in those early years. The Chattahoochee River ran wilder and freer than it does today, unencumbered by a Lake Lanier and Buford Dam that would not exist for nearly forty years. The woods in between the hills along the river have been described by old-timers from that period as dense and dark, with an occasional family hamlet or moonshine still hidden in the valleys that still evoke a lot of mystery and trepidation.

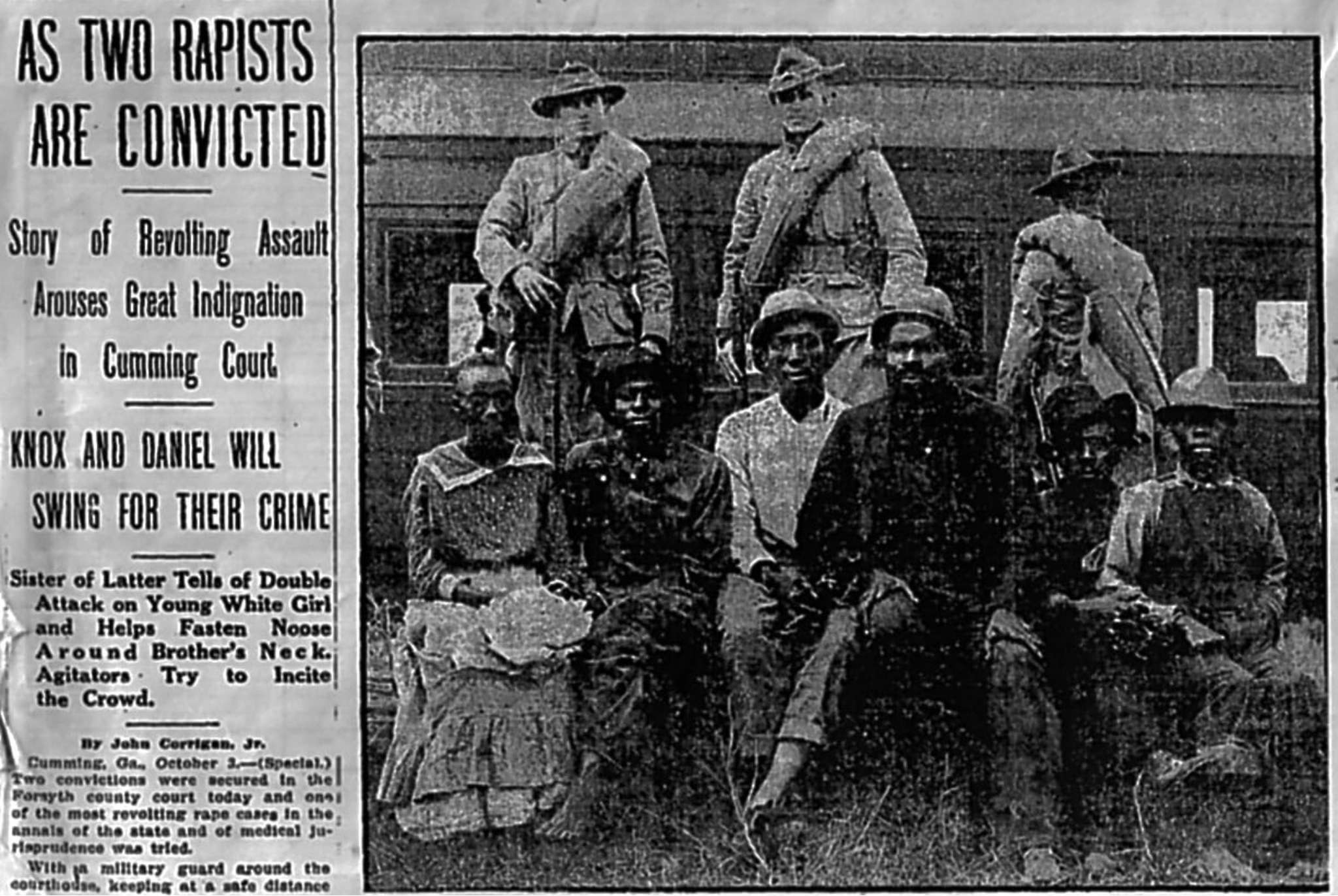

Cumming, in 1912, was a city that wanted to be on the rise. Every city wanted a railroad. Cumming looked to the success of cities like Buford, which had been founded on a railroad in 1872. Community leaders made every effort to appear New South and progressive to railroad investors – the prospects were positive until something happened that forever altered Forsyth County’s future. Five young black male farm laborers – Toney Howell, Isaiah Pirkle, Fate Chester, Johnny Bates, and Joe Rogers were accused of sexually assaulting Ellen Grice on September 5. Nearly a week later, another woman, Mae Crow was found sexually assaulted and murdered. Oscar Daniel, Jane Daniel, Rob Edwards, Ernest Knox, and Ed Collins were all arrested for suspicion of murder. Mob rule prevailed along the Chattahoochee River, followed by the lynching of Rob Edwards. Ernest Knox and Oscar Daniel would later be sentenced to hanging in early October. It is estimated that between 5,000 and 6,000 gathered to watch the execution.

Community leaders had the foresight to house the suspects, from both instances, in Atlanta before trial. They were transported back and forth by train to Buford. The remaining suspects, on October 2 after arriving at the Buford Train Depot, made their way by wagon through the crossroads we now call Sugar Hill. It is hard to fathom the trip by wagon between Buford and Cumming in the early 1900s. We don’t know if it was cool or warm. We don’t know anything about the weather, but I think we can all imagine the heat of fear and anxiety that the suspects would have felt as they made their way through the woods and across the Chattahoochee River. The wagon trip would have been longer than today, but not long enough in their minds.

There was a lasting legacy for Forsyth County and surrounding communities on both sides of the Chattahoochee River that lingered longer than just these several months of mob rule and violence. Soon after the executions of Ernest Knox and Oscar Daniel, all of the nearly 1,100 black residents were forced out of Forsyth County. Many fled to Gainesville in Hall County and other communities that were away from the border with Forsyth County. These men, women, and families had established churches, traditions, and a community that they were forced to immediately give up – in some cases overnight.

A hidden history exists that we can easily overlook. The waters of time, like the Chattahoochee River and Lake Lanier, can easily wash over certain aspects of our collective past. I cannot erase the images that were in my mind when I read Patrick’s book. These images still linger. His book reopened a history that many would like to leave in the past, but that we should not forget.

— By Brandon Hembree