If you have ever explored a cemetery in Sugar Hill, Buford, Suwanee or any community on the edges of Lake Lanier, you have likely noticed relocation markers. It might be morbid curiosity, an appreciation of history, or both that make these discoveries intriguing. Questions might arise about their original location, and we automatically frame a picture in our mind of a cemetery or a plot of land that is now deep under murky water.

Lake Lanier is a man-made lake that provides drinking water, hydroelectricity, and recreation opportunities to residents in Sugar Hill, Gwinnett County, and the rest of metro-Atlanta. After years of careful planning and strategic property acquisition beginning in 1948 by the Federal government, Lake Lanier was officially created in 1957 with the completion of Buford Dam by the Corps of Engineers. It took nearly five years for the lake to settle and reach its intended boundaries with surrounding properties. Lisa Russell has written a great book titled “Underwater Ghost Towns of North Georgia” that explores the topic of displacement of individuals and the flooding of various towns that were in the Lake Lanier footprint. Lake Lanier impacted not only the landscape but also shaped the history of many communities in its path like Sugar Hill.

Nearly seven-hundred families were displaced by the project. Large farms, orchards, roads and buildings were covered by water. Less common knowledge is that the incoming waters of Lake Lanier also caused the displacement of many existing cemeteries and family graveyards. It is estimated that nearly twenty cemeteries were impacted by the creation of Lake Lanier. Cemeteries were moved to higher ground in areas around the lake’s future boundaries. Hundreds of burials, mostly from small family graveyards, were disinterred and reinterred in cemeteries in Sugar Hill and other surrounding communities.

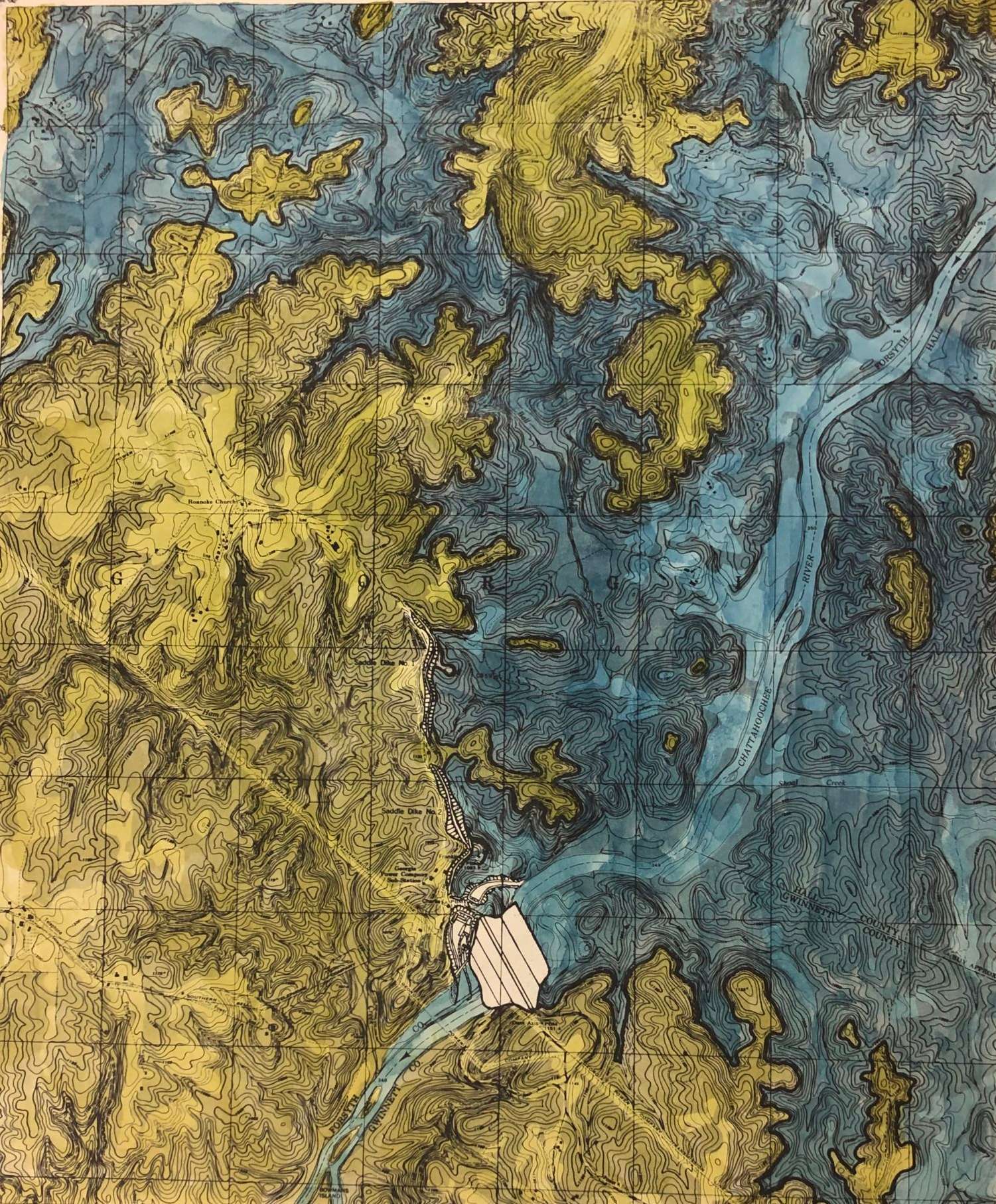

These removals were in no way a haphazard effort. The Corps of Engineers, through a firm called Park Aerial Surveys, developed very detailed maps as a way to estimate the boundaries of Lake Lanier. Some of these maps exist today and are in the possession of the Sugar Hill Historic Preservation Society. The maps show elevations, future islands, and the boundaries of the lake after a “maximum power pool” of 1,070 feet. In addition, the renderings show old creek beds, the original bed of the Chattahoochee River, and nearby churches and cemeteries. The project, then called the Buford Dam and Reservoir Project, was an engineering marvel for its time. Every effort was made to relocate family graveyards and church cemeteries, and as often as possible they were moved to where other family members were buried.

At Island Ford Baptist Church Cemetery there is a flat ground marker, which is hard to find. It reads: “In Memoriam. 3 graves moved in 1957 from within Buford Dam and Reservoir project. Included are graves from Thornton Cemetery and Shoal Creek Church Cemetery.” Two of the three burials are believed to be William Pruett, who died in 1876 in Sugar Hill, and his wife, Mary Bradford Pruett. Both were relocated from Thornton Cemetery. They were perhaps relocated to Island Ford because of its proximity to William’s place of death. In Sugar Hill Historic Cemetery, there is also a relocation marker for Bonnie Peppers. Bonnie’s remains were removed from Shoal Creek Church Cemetery to be near other members of the Peppers family. In cases where permission was not given to relocate, graves were left to be covered by Lake Lanier. The cemetery for Spencer Hill Baptist Church, a predominantly black church, was relocated in its entirety to another predominantly black church in Buford called Union Baptist Church. The Gwinnett Historical Society has information on many of these relocated graves.

For those of us that live near or utilize Lake Lanier, there is a permanent element of mystery that lurks just under the surface of this reservoir that is so important to our community. Since its creation, these undercurrents have been told through stories or written about in articles or books – some considered to be wives’ tales or ghost stories. There are stories, though, that are real stories like the stories of above – stories of historical significance that should be told so that the past is not covered up by time or Lake Lanier.

— By Brandon Hembree