This is the fifth and final article in a series relating the history of Lake Lanier and Buford Dam and coinciding with a special exhibit on Lake Lanier presented by the Sugar Hill Historic Preservation Society at the city’s history museum.

Buford Dam was completed in early 1956, which meant the reservoir known as Lake Sidney Lanier could begin filling up. Numerous bridges and roadways would be impacted as the lake levels began to rise. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had the daunting task of determining which bridges and roadways would be relocated and which ones would be swallowed up by the lake.

Several factors were taken into consideration when determining whether or not bridges and roadways below the flood line were going to be replaced or removed. One such factor was just how often the roadway was used. In today’s world, traffic studies on particular roadways are conducted by the government placing small black tubes across the roadway that are called portable automatic traffic recorders. Vehicles drive over the tubes and the data is recorded.

According to Robert David Coughlin’s book “Lake Sidney Lanier ‘A Storybook Site’: The Early History & Construction of Buford Dam,” traffic studies back in the late 1940s and 1950s were a lot more hands-on. The government would place men on or near the bridges that were up to be replaced or removed altogether to count the number of vehicles that traversed the bridge in a specified time frame.

Naturally, the findings the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers presented to the local and state governments and residents did not always find favor. Some local and county governments were even compensated for the destruction of the bridges they had built when said bridge was not relocated.

Clark’s Bridge was set to be scrapped, but Hall County fought back against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The county had hired an engineering firm that said the complete removal of Clark’s Bridge would cost local residents an additional $26,000 per year to travel to an alternate route. In the end, a compromise was reached, which had the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers paying $285,000 toward the new Clark’s Bridge, while Hall County would have to pay out between $40,000 to $90,000.

Years later, Hall County would once again take the government to court over the roads and bridges that were lost due to the construction of the lake. The county claimed the government had not adequately replaced the roads and highways that disappeared to make way for the reservoir. Hall County eventually won $1.7 million dollars in federal court over the matter. The county would use part of this money to pay for the construction of McEver Road, which was essentially an extension of Peachtree Industrial Boulevard coming up out of Gwinnett County.

Buford Dam Road was the first of many road projects. The construction of Buford Dam Road cost $2,836,712 and was built by Groves, Lundin and Cox Inc. of Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The roads and bridges were worked on starting around 1951 all the way to 1957. The projects on the south end of the soon-to-be lake were the first ones to be worked on, while the bridges and roads on the northern end of the lake would be the last to be constructed as it would take years for the lake to form on the north end.

On Feb. 1, 1956, the gates of the intake structure at Buford Dam were closed and the lake began the long process of filling to full capacity. Lake Lanier would not reach its intended full pool until Aug. 1, 1958. This was approximately a year behind schedule. The delay was caused by drought and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers intentionally slowing the rising water. The intentional interruptions were done when water levels threatened various worksites along the project.

The official dedication of the lake took place the day the gates were closed on Feb. 1, 1956. Twelve dignitaries simultaneously flipped switches that closed the gates of the intake structure of Buford Dam. A bucket of water was then taken from Lake Lanier and presented to the manager of Atlanta Water Works Association, Paul Weir, as a gift to signify the future relationship between the reservoir and the city of Atlanta.

A motorcade then made its way from the dam to the city of Buford public square in between Garnett and Scott Streets where an unveiling ceremony took place. A cylindrical monument sits on the square that was bored out of solid rock that was 192 feet below where the intake structure sits. Four bronze plaques honor the people who tirelessly worked to bring the reservoir to fruition, and the monument also includes statistical data about the Lake Sidney Lanier project.

The monument still stands in the town square as a reminder of the commitment of a handful of people dedicated to the betterment of the North Georgia area. Atlanta and much of North Georgia would not be the same without Lake Lanier. The lake pumps billions of dollars into the local economy each year, it supplies drinking water to 5 million people, produces hydroelectric power, provides flood control and a reliable water level downstream. Simply put, Lake Lanier made North Georgia the economic powerhouse it is today.

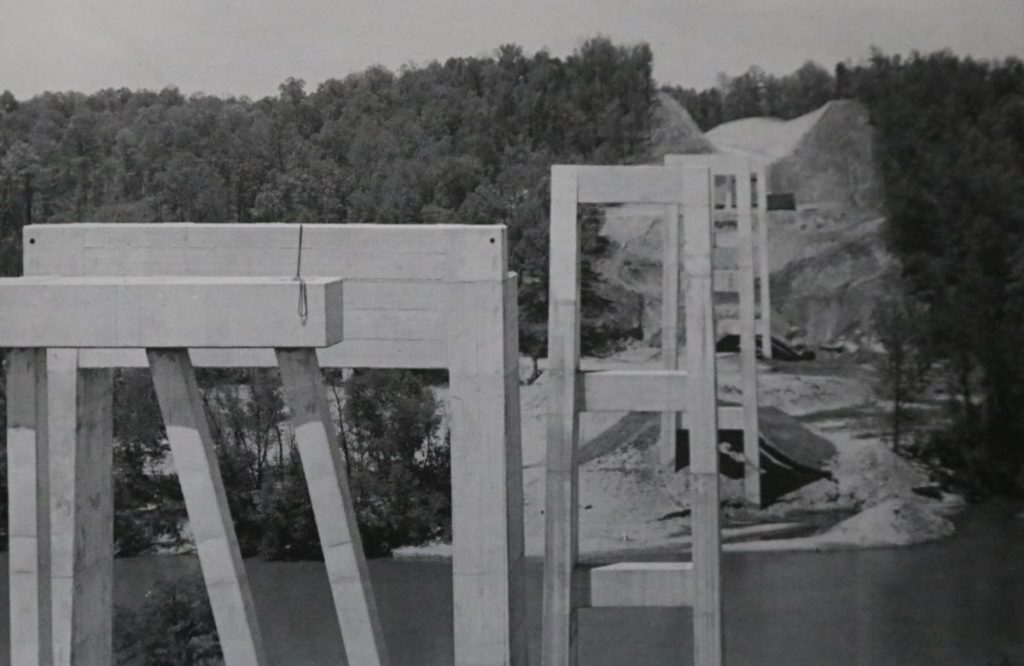

Featured photo above: On Friday, May 6, 1955, the pier substructure on Brown’s Bridge was completed. The view is looking toward the Forsyth County abutment. Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Mobile District)